A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

Arthur Hardy: Mardi Gras and music

-

By Peter Finney Jr.

Clarion Herald

For those of a certain age – and you know who you are – Arthur Hardy has been the public face of Mardi Gras for nearly a half-century.

Hardy annually cranks out his comprehensive Mardi Gras Guide, which chronicles the who, what, when and where of every Carnival parade, some of which you’ve heard and some of which you haven’t.

Hardy is so well-versed in Mardi Gras lore and practice that he can spout from memory each krewe’s artistic theme and “signature throws” as though he were reciting the alphabet. He knows all the players behind the masks.

A master brass player

What’s less known about Hardy is his background as an instrumental musician – he played the trumpet, baritone and trombone as a student at Warren Easton High School and at Loyola University New Orleans – and as the band director at Brother Martin High School from 1973 to 1989, which fueled his love for the history and traditions of Mardi Gras.At Brother Martin, Hardy worked with the late Marty Hurley, the person he always considered his “co-director” and “the greatest teacher I ever knew,” and he was passionate about teaching students of all abilities.

“Being in a band is a lot like being on a football team,” Hardy said, recalling how when he got the director’s position in 1973 he spent the summer preparing band students for the football season.

“The discipline that’s taught, the spirit, the amount of time you spend together, the bonding and working together are so important. And, you win some and you lose some. But it’s that idea of being part of a group and thinking of people other than yourself.”

Besides directing the band, Hardy taught instrumental music at Brother Martin.

Music led to storytelling

In 1977, four years after he came to the school, Hardy looked at his bank account and growing family and fell into an opportunity to produce a Mardi Gras preview magazine that might supplement his income to provide for a growing family.He went to Sacred Heart Brother Donnan Berry, the Brother Martin principal, to ask permission to take on the side project.

“The Sacred Heart Brothers could have easily stopped it in its tracks, but they blessed it,” Hardy said. “Then, once the magazine really took off, I became part-time and they allowed me to work a half-day and do my business the other part of the day. They very easily could have said, ‘You’re either a teacher or a Mardi Gras magazine producer. You have to make a choice.’”

Emotion-filled decision

By 1989, the Mardi Gras Guide was doing so well that Hardy felt he had to make a choice about whether or not to continue teaching “because I couldn’t continue doing both well.” He decided he had to step away from the classroom.“I cried like a baby when I resigned,” Hardy said. “It was the hardest thing in my life to walk away from that job, and I still miss it, but I still feel like I’m part of the family. I’m welcome at Brother Martin. It’s such a special place.”

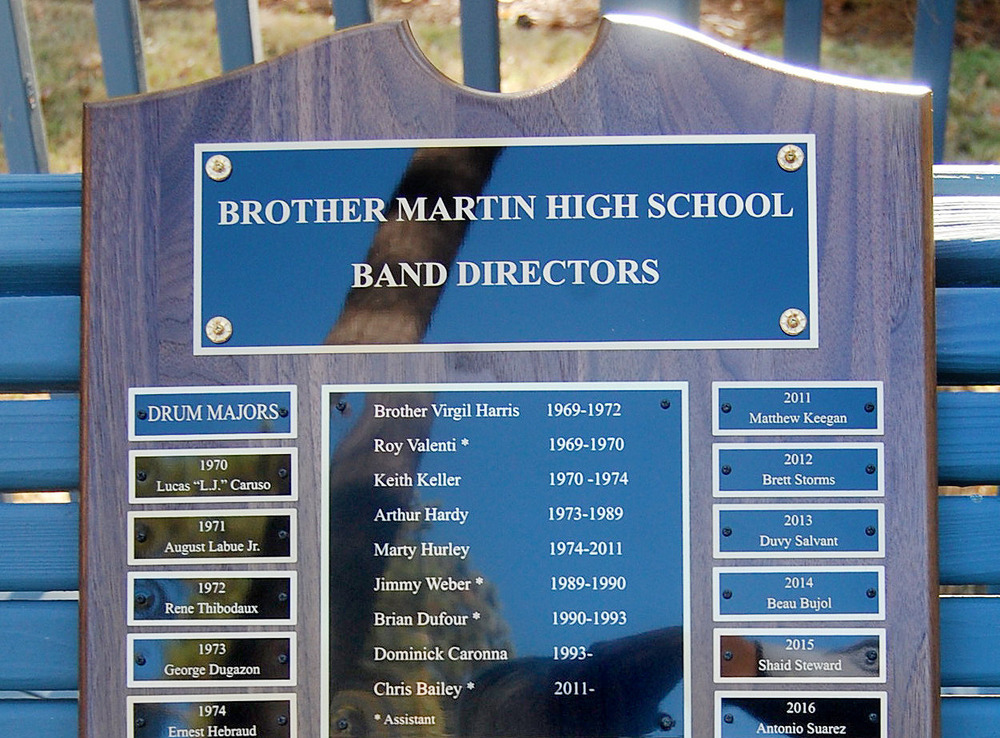

Hardy’s love for Brother Martin was showcased at the Crusaders’ homecoming game in 2021 when he provided a large plaque containing the names of every Brother Martin band director and drum major in the school’s history.

“It was a combination of my two greatest loves – history and music,” Hardy said. “I just thought it would be a nice way to commemorate the musical leadership from both the directors and the students through the 50 years of the school.”

Parades, music inseparable

As Hardy reflects on the return of high school bands to the streets for Carnival – after a one-year COVID-19 hiatus – he knows one thing with certainty.“A parade without bands really loses a lot,” Hardy said.

Hardy has two classic memories of his tenure as band director. In the late 1970s, when the Krewe of Hercules was forming at the Pontchartrain Beach parking lot, it was so cold that Hardy had to make a parental decision.

“I was wearing thermal underwear, two pairs of socks and a hat, and I had never been so cold in my life,” Hardy recalled. “So I told Marty, ‘We can’t morally ask these kids to march in this parade. This is brutal.’ I had to tell the captain that we couldn’t endanger the kids’ health. Their mouthpieces would get frozen to their lips. I thought we might get some pushback, but we didn’t because it was the right decision.”

A long way to Tipperary

During another Gentilly parade – Pandora – a band member known for sometimes being “a goof-off” came up to Hurley with a plea halfway through the five-mile route.“I don’t think I can go anymore,” he said.

“What’s wrong?” Hurley asked.

“I think I’m having a heart attack.”

“What do you want me to do, son? We’re halfway through the parade. You might as well march to the end or walk back.”

“Well, I could go to my grandmother’s house.”

“Where’s your grandma?”

“Right there. She lives across the street.”

“Get out of here! You’re marching the rest of the parade.”

Hardy said studying music has been shown to help students improve their mathematical and logic skills, but it goes far beyond academics.

“It’s just kind of a life lesson – being part of something greater than yourself,” Hardy said. “I always thought that teaching musical notes was the least important part of my job. I was trying to reach the kids. It’s a part of the family. There’s something about that relationship that’s forever.”

Brother Martin’s current band director Dominick Caronna, a 1985 graduate, was Hardy’s student.

“I remember him being on that podium and teaching us music and explaining things,” Caronna said. “I also remember when we used to play football after band class with Arthur and Marty. I could never understand how nimble Arthur was. They would get us running around in circles.”

Caronna said maintaining physical fitness is one of the keys to a marching band’s performance level.

“We try to get the students to take responsibility for their own health in terms of walking,” Caronna said. “We’d like them to walk a mile around their home just to get their core strength up, because that equipment can get pretty heavy after a while.”

While it’s natural for all bands in the New Orleans area to match their reputation with that of the legendary St. Augustine Marching 100, Hardy said “there is room for everyone.”

“St. Aug has a different style than Brother Martin’s, which is more of a military style,” Hardy said. “St. Aug and Warren Easton have more of a show style, and there’s room for everything. St. Aug’s dedication, the pride they have and the hard work they put in make them very exciting, and there’s no doubt about it, they’re a crowd favorite.”

As a Mardi Gras historian, Hardy said most people know that St. Aug’s Marching 100 broke the color barrier in Rex in 1967 when they became the first African-American band to march in the parade.

“It meant a lot not just to the kids in the band but also to the whole community because it was past time for it to happen, and Rex gets a lot of credit for that,” Hardy said. “But what some people don’t remember is that four or five days earlier, St. Aug marched in the Freret parade. So, really, Freret was the first parade. It’s hard to think back now and say that was a big deal because we’ve come so far, thank God. You might say now, ‘Why would that be something?’ – but it was.”

And now, after a year of silence in the streets, the music and the floats and reverie will return to Carnival.

“This is absolutely big,” Hardy said. “There’s never been a more anticipated Carnival season ever. This is our comeback. We’re back.”

Bigger even than 2006, the year after New Orleans nearly was washed away?

“This year is different than 2006,” Hardy said. “There’s very little comparison. We still needed it (in 2006), and it was great that we did it and it was important. Back then there was the question of whether we could do it. Here, it was a question of, ‘Will we be allowed to do it?’ Thankfully we’ve made the decision that we can, and I hope we do it safely.”