A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

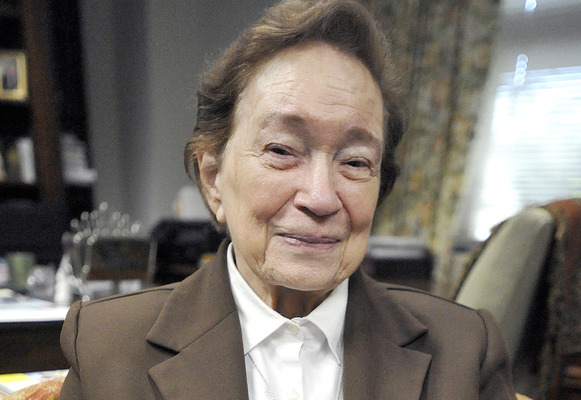

Sister Camille Anne: Mount Carmel's Mount Rushmore

-

By Peter Finney Jr.

Clarion Herald

It was September 2005, and Sister of Mount Carmel Camille Anne Campbell, the Mount Rushmore of New Orleans Catholic educators, was in a conference room of the Embassy Suites in Baton Rouge with a small team of her fellow administrators and teachers.It was lunchtime, and Sister Camille Anne was assessing the moonscape of a devastated city 80 miles to the south as well as the tomatoes in her salad.

All of a sudden, she lurched forward.

“My head fell into my plate at the lunch table,” Sister Camille Anne recalled, the moment from Katrina that continues to remain a blur. “I woke up in the hospital. I think they ended up saying it was stress-related.”

Who could have guessed that?

Nine years after a 1996 quadruple heart bypass, Sister Camille Anne had been responding in the days after Katrina in the way she always tackled bad news, stepping foot-first into the breach.

In this case, the breach of the 17th Street Canal less than a mile away became the catastrophic gateway for 10 feet of water and sludge to pour in and swallow her school. Sister Camille Anne had only a mop, but she kept swiping. Some privately might have wondered if she were tilting at windmills.

Sister Camille Anne was determined to reopen in January 2006 – to be the first school at Ground Zero to welcome students back – but in order to do that, she needed clean water to flush away the grime and provide sanitation for an army of restoration workers, who were camping out in tents on the campus.

The only option for preserving that timeline was to drill a well 1,100 feet deep.

“To me, the most amazing thing was to be able to get up in the morning and say, ‘God, this is something we have for you, so you’re going to get us through this day – show us what to do,’” Sister Camille Anne said. “And, every day we would get up and just say, ‘OK, what are we going to do today?’ You couldn’t look at the whole thing because you would not have come to school. And, then, we began to see the possibility of, ‘Yeah, it can happen. It can come back. We can be OK.’”

Mount Carmel reopened on Jan. 17, 2006, with 1,038 of its 1,253 students.

“It’s been incredible, but I think the gift was just to get up and say, ‘OK, God, what do we do today? Show us, lead us,’” Sister Camille Anne said. “Every day, we were getting led.”

In her more than 60 years as a Catholic educator, Sister Camille Anne has been decorated many times for her school leadership. At the recently concluded annual conference of the National Catholic Educational Association, she was one of 10 administrators across the U.S. to receive the NCEA’s prestigious “Lead. Learn. Proclaim.” Award. That honor represents the triple mission she has been living out daily since surrendering her childhood dream of becoming a physician in order to care for souls.“Lead, learn, proclaim – that’s been my religious life,” she said. “I have always tried to lead people to Jesus, to know the Trinity. I wanted to learn everything I could about people, about myself, about our church and about how Jesus tried to teach us to live and about what his mother said a woman should be.

“And, then, there’s ‘proclaim.’ That’s what you do when you stand up in front of kids in the classroom or end up in front of their parents or in front of teachers or in front of all kinds of people who ask you to talk. You go and speak.”

Sister Camille Anne, a native of Jackson, Mississippi, has never been bashful about speaking her mind, although a longtime friend describes her as “quick to listen, slow to speak.”

“I take my time to know what’s meant,” Sister Camille Anne agreed. “You shouldn’t judge quickly just because you heard a few words.”

Her father, Charles Campbell, an attorney, died when she was just 3 months old. Years later after her widowed mother remarried, she saw a younger sister gain strength after being born prematurely, and as a teenager, the idea of going to med school intrigued her.

“I thought the doctor saved the baby, but it was really God who saved the baby,” Sister Camille Anne said. “That began my interest in medicine, but I could not figure out the brain and the soul. There weren’t a lot of female physicians in those days, especially in the South, so that made it even more appealing.”

Vocation seed planted

The thought of a religious vocation, however, had crossed her mind. On a retreat at St. Joseph High School, a classmate was late getting back to the group, creating concern, and Camille Anne said something like, “Let’s say a prayer for her.”

“One of the people in the room said, ‘You know, you ought to be a sister. You’re always caring about everybody, and now you want us to pray,’” Sister Camille Anne said. “That stuck with me.”

In the summer after her senior year of high school, she injured her ankle in a sailboat accident, and she couldn’t walk. College and potential medical school would have to wait. Now living with her family in Abbeville, Louisiana, Camille Anne spent her days escorting her two younger sisters to and from Mount Carmel Elementary School and attending daily Mass.

It was Mother Francis, the superior of the Mount Carmel community, who spotted the faithful teenager one day and suggested that she try out the Mount Carmel novitiate in New Orleans and “then decide if you want to be a sister.”

“I figured I could go and get a year of college and see if I liked it,” she said.

She did, and she stayed. In the early 1960s, she was a sixth-grade teacher at St. Dominic School in New Orleans, teaching all subjects to a classroom of 35 students.

“I loved it,” she said. “It didn’t take me long to realize it was a gift that God gave me to realize that I was enjoying watching these children grow. It was a vocation to know that we were here to do something good on Earth to help other people.”

Teacher’s ‘heart’ contact

Long before the days of differentiated instruction, Sister Camille Anne developed on-the-fly teaching methods that worked wonders.

“I had one girl move her desk by my desk,” she recalled. “She just needed to make sure I was looking at her because she’d behave if you were looking at her. The main thing is you have to let the students know you care about them. You don’t just say, ‘All right, all of you, stop doing this!’ You look at them and address them. That eye contact becomes heart contact. It’s like, ‘Wow, she might care!’”

After years as an elementary principal, Sister Camille Anne succeeded Mount Carmel Sister Mary Grace Danos as Mount Carmel principal in 1980 and has been president-principal or president ever since. She has master’s degrees in math, religious education and counseling. She passed up another chance to get a medical degree in the 1970s because “as a sister, I wanted people to learn and know about Jesus and his mother.”

In January 2022, she got home late to the motherhouse in the rain and was so tired she hurried to slip on her pajamas, putting one foot and then the other foot into the same leg. She fell and broke her hip. One week later, in her rehab room, she scooted over to the bathroom and blacked out.

“I had this bright white light, but then it just started going totally black,” she recalled. “All I could say was ‘God!’ I don’t know who found me or what they did with me.”

When she went into surgery for an aneurism the next morning, her anesthesiologist was the husband of a Mount Carmel graduate. Two days after the surgery, the neurosurgeon came in and told her, “The Lord kept you here for a reason.”

And then the surgeon asked what was on her mind. For the next seven minutes, barely taking a breath, Sister Camille Anne told him about all her plans for converting the former motherhouse into new classrooms for religion, fine arts and choral and instrumental music.

There she was, “proclaiming” again, from her hospital bed.

“That’s why you are here, Sister,” the neurosurgeon said.

Sister Camille Anne’s former bedroom in the motherhouse on Allen Toussaint Boulevard was on the fourth floor.

“The view from there is just magnificent,” she said. “It’s like you’re in the sky. You look out the window, and you see the tops of the trees and the blue sky.”

Her bedroom for the last 40-plus years will become a studio where young art students will paint their own dreams.