A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

St. Joseph the Worker Church spotlights heroes and heroines of Black history

-

By BETH DONZE

Clarion Herald

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, helped jump-start the American Civil Rights Movement.But what’s far less known is that nine months before Parks made her stand – in that same city of Montgomery – a 15-year-old Black girl named Claudette Colvin also refused to cede her bus seat to a white passenger and suffered the indignity of an arrest.

The amazing story of Colvin’s Black history “first” was brought out of the shadows for congregants at St. Joseph the Worker Church after the 10 a.m. Mass on Feb. 6 in conjunction with the parish’s ongoing celebration of Black History Month.

During a poignant reenactment of the event staged just below the altar, “Claudette Colvin” – portrayed by teenage parishioner Baileigh Goines – ignored the irate faces of her fellow passengers and defiantly remained in her seat. As a siren sounded, police officers handcuffed Colvin and hauled her off to the station for booking.

Helped ‘destroy’ concrete barriers of segregation“Black history is American history,” noted Father Sidney Speaks, St. Joseph the Worker’s pastor, preparing his flock for five consecutive Sundays of exposure to black heroes and heroines, some of whom are far from household names. “Church, let us always know that Black history never ends in February; it happens every day.”

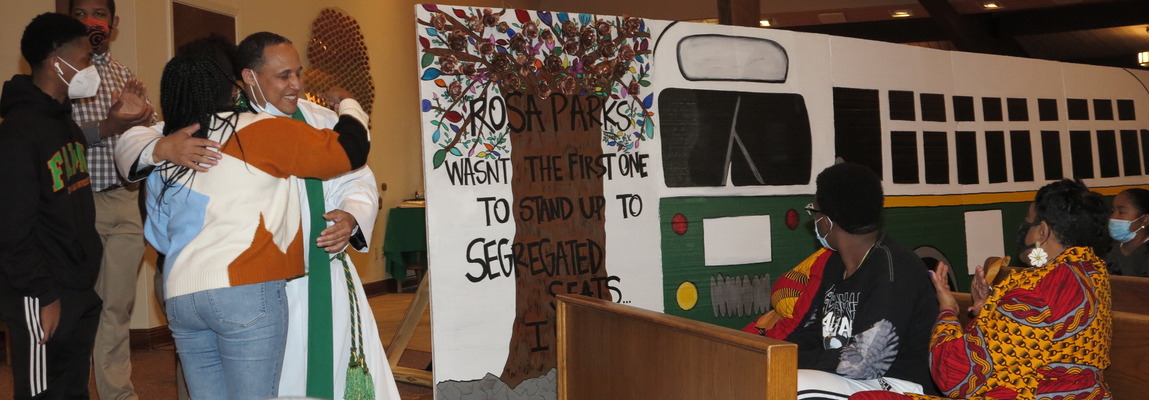

Following the skit on Colvin’s act of civil disobedience, a more than 22-foot-long painted mural depicting a public bus, executed by parishioner Lauren Batiz, was unveiled by St. Joseph the Worker’s confirmation candidates.

Batiz, who was familiar with Colvin’s story from a young age through her family and church, said the mural’s creation was inspired by Colvin’s willingness to hold fast to her principles in the face of an unexpected challenge. She said Colvin’s story shows how even young people were able to detect that segregation was wrong and to speak out against the status quo.

“To know, in Black history, the people who were young and stood up for things is something that’s very important to foster in the kids of today, so that they can grow up and then teach it – that’s how we keep our history going,” said Batiz, 30.

An oak tree, sprouting gold roses and multi-colored leaves representing the diverse cultures of the African-American people, bursts out of the concrete in Batiz’s mural – the artist’s nod to Colvin’s role in helping people of color to bust through the “weight” of segregation and tell the world that skin tone should not restrict any human being’s freedom of movement.

The tree’s trunk holds a quote from Colvin herself: “Rosa Parks wasn’t the first one to stand up to segregated seats ... I was.”

“The normal saying is, ‘From the concrete, a flower can grow,’” Batiz said. “But when I thought about Black history, I thought about a flower and the fact that you can easily kick that over; but when you see a tree growing out of the concrete, it can’t be taken down; it destroys the ground around it. I feel that honors Claudette and what she did – ‘They didn’t keep me down; I’m not moving; I’m going to grow where I’m planted.’”

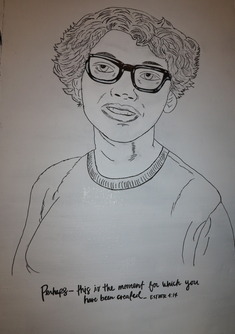

A portrait of Colvin, a collaborative drawing executed by Batiz, her mother Yvette Dinvaut, and her cousin, Damon Bowie, anchors the tail end of the bus. An Old Testament quote from Esther 4:14 is inscribed below: “Perhaps this is the moment for which you have been created.”

“(This biblical passage) really signified to me that Claudette was created to do something in that moment, in the same way that Esther was brought up to be a queen,” Batiz said. “God called and created us all to do something great. You may not know what that is; you may not know how it’s coming to you; but if you remain close to him (and) if you stay near his spirit, he will reveal that to you, and you will do great things.”

Colvin, Batiz said, “changed the structure of segregated seats on buses. I think we’re all called for a moment as special as that.”

More achievers to be recognized

Every Sunday through March 6 following the 10 a.m. Mass, additional Black history giants from various fields will be honored at St. Joseph the Worker Church (455 Ames Blvd. in Marrero) through skits, music, narratives and the visual arts.

Recognized alongside Claudette Colvin at the Feb. 6 program was Frederick McK

inley Jones, a WWI Army veteran and electrical engineer who invented refrigerated trucks for the long-haul transportation of perishable goods. Jones, the co-founder of Thermo King, held more than 60 patents at the time of his death in 1961. A facsimile of his revolutionary cooling unit, crafted by St. Joseph the Worker parishioners, was unveiled during the related skit on his life.

The remaining honorees and dates of St. Joseph the Worker’s 2022 Black History Month program will be:

• Jane Bolin, the first African-American female judge; Gen. Benjamin Davis Sr., the first Black general of the U.S. Army (Feb. 13).

• Althea Gibson, the tennis great who became the first African American to win a Grand Slam title (in 1956) and went on to win nine additional Grand Slam titles in both singles and doubles play; Josh Gibson, one of the greatest power hitters and catchers in baseball history and who was known as the “Black Babe Ruth” due to his more than 800 home runs in the “Negro” baseball leagues; and two African-American bands: Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes; and Martha and the Vandellas (Feb. 20).

• Henrietta Lacks, whose amazingly viable cells, donated post-mortem, created a line of cells that informed the development of vaccines and are used to study the effects of toxins, drugs, hormones and viruses on the growth of cancer cells without experimenting on humans; poet and author Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black person to receive a Pulitzer Prize (Feb. 27).

• Dr. Philip Emeagwali, hailed as one of the fathers of the Internet and who helped build the first supercomputer; Bessie Coleman, the trailblazing Black pilot (March 6).

Throughout the month, three symbols of the African-American experience will sit at the foot of the altar: a set of shackles, symbolizing the enslavement of people of color; a graduate’s mortar board, representing the benefits education has brought to the lives of African Americans; and a hymnal containing sacred songs that bolstered the spirits of Black faithful in America.