A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

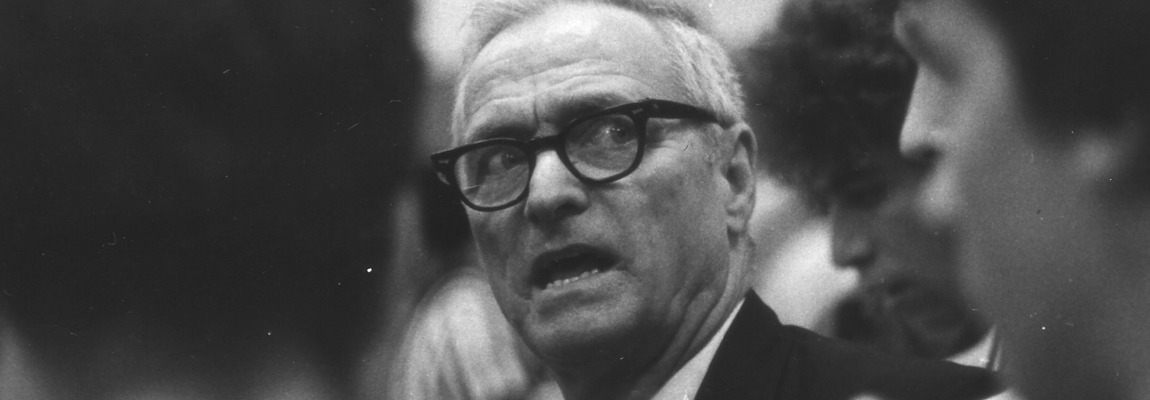

St. Aug's white 'grandfather' had an eternal message

-

In an era of Artificial Intelligence and cloud databases, Charlie Myers, 99, preferred pencils with erasers and spiral-bound notebooks.

Myers grew up within a culturally scrutinized minority in Laurel, Mississippi – he was, after all, a Catholic in the buckle of the Bible Belt.

As an inexperienced football coach in the 1940s at Laurel High, Myers wanted to improve his skills, so he set up a series of surreptitious meetings with Stumpy Springs, coach of the all-Black Oak Grove High School.

For obvious reasons – a minor footnote being that Mississippi’s Ku Klux Klan grand wizard lived in Jones County – the white and Black coaches couldn’t meet publicly at a coffee shop. They decided to talk football strategy in the back room of Rose Jewelry, owned by a Jewish man.

“At the time, Catholics were right up there with the Jewish and Black population,” Bill Myers, one of Charlie’s nine children, said of his dad, who died Feb. 6.

In a life of understated grace, fair play and pencils with erasers, it is difficult to etch in granite what might have been Charlie Myers’ most impressive legacy.

In addition to his civil rights work well before its appointed time, he forged interfaith meetings for Laurel teenagers in the 1940s because “no one knew anything about the other.” Fifteen weeks during the school year, students attended talks at different churches to chip away at religious silos. Charlie, himself, lived across the street from Immaculate Conception Church in Laurel.

On a teacher’s salary, he and his wife Carolyn put their nine children through LSU. They attended different Sunday morning Masses – he would go to the 7 a.m. at St. Stephen’s Church, and Carolyn went to the 9 a.m. at Our Lady of Lourdes Church on Napoleon Avenue – to keep the Myers clan under control through shift management.

“I don’t know how we did it, but we managed to get by,” Charlie said in a 2009 interview with the Clarion Herald.

Myers, who coached virtually every sport, taught his basketball players not to make excuses or blame the refs for a loss. “They don’t miss as many calls as we miss foul shots,” he told them.

In the midst of his coaching and teaching duties at New Orleans Academy (NOA) from 1953 to 1986, he also found time to officiate basketball and football games. The brain was his human computer’s motherboard: With no access to email or cell phones, he created – and re-created – the officiating schedules in basketball for 59 years and in football for 35 as assignment secretary.

Myers was so adept at erasing no-shows that he could find a replacement official for a Saturday morning game even late on a Friday night.

“He knew all the bars we stopped at after games,” one official said. “The bartender would yell out, ‘I have a Charlie Myers on the phone, and he needs two officials for a game tomorrow.’ We tried to move bars so he couldn’t find us, but he always did. We never could figure out how he knew.”

“It was all in this spiral-bound notebook,” Bill Myers said. “He even had ‘scratch list’ in his head. These were the officials that coaches didn’t want coming to their games again, and he tried to honor it.”

Charlie’s family did not find out until last Thanksgiving that he was one of the refs who officiated the “secret” basketball game played between St. Augustine and Jesuit in 1965 at a time when Deep South segregation did not allow Blacks and whites to compete against each other. The game was immortalized in the 1999 movie, “Passing Glory.”

Myers unlocked the story of his assignment for the first time to Father Tony Ricard, St. Aug’s campus minister, and Deacon Uriel Durr, who played for him at NOA.

“No one had been brave enough to ask him, so I asked him, ‘Were you the ref?’” Father Ricard said. “He looked up at me with a smile on his face and said, ‘They called about the game and asked me if I could send my two best referees. I assigned one guy – and then I assigned myself, too.’”

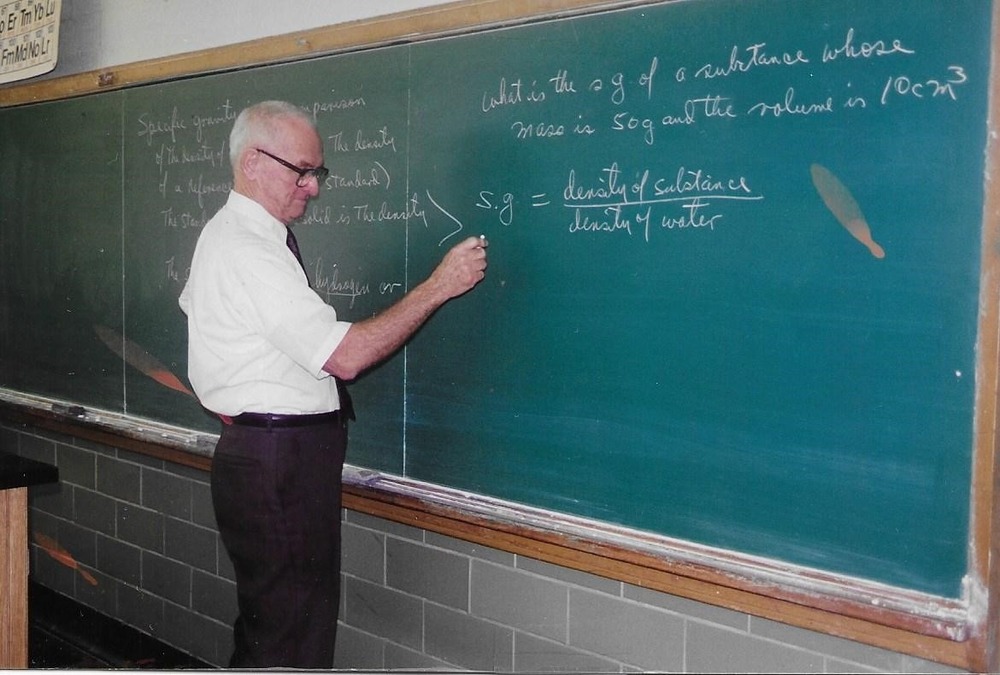

When New Orleans Academy closed in 1988, Myers discovered from St. Augustine principal Al Peychaud that the school was looking for a chemistry teacher.

“I told him, ‘I know somebody who might be interested,’” Charlie said.

Myers had assigned himself again.

At the age of 66, Myers wound up teaching chemistry, Latin, biology and Earth science and later helping out in the St. Augustine office for 30-plus years.

At the age of 66, Myers wound up teaching chemistry, Latin, biology and Earth science and later helping out in the St. Augustine office for 30-plus years.He was so beloved at St. Augustine that the school installed a personal phone line for him so that he could continue to do his officials’ scheduling work during off periods.

Even after he lost his two-story home in Lakeview to Katrina in 2005, Myers returned to St. Aug and worked full mornings as the attendance officer, well into his late 90s. When it was unsafe for him to come to school during the COVID pandemic, he kept in touch by answering emails.

“He told me, ‘I just took a little break during the pandemic,’” Father Ricard said.

“Mr. Myers was an amazing man,” said Suzanne Davidson, human resources director at St. Augustine. “If a kid came in late and he had to write up a slip, he didn’t have to ask his name because he knew who he was.”

As always, it was the little things that a father notices intuitively that defined Charlie Myers. When the rest of his NOA players were excited because they had won their final game of the season, Myers spied one of his seniors sobbing at the rear of the bus.

It was the kid’s last game.

“Congratulations on a great career, son,” the coach told him, wrapping an arm around his shoulder.

In the same way, Father Ricard often would see Myers in the office and throw both arms around him.

“He was everybody’s grandfather,” Father Ricard said.

“He had a vocation, and he was answering a call from God,” he added. “Think about this. It was the 1940s, and he was meeting with Blacks at a Jewish store. This man was at the forefront of civil rights. This man was participating in civil rights even before there was ‘Passing Glory.’ He was doing his own thing to bring people together.”

Myers never talked about himself.

Get out a pencil and write it down.