A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

The usher who collected nothing but the truth

-

One night in the 1970s in his Metairie home, Leon Drew clicked on his TV and saw an Al Copeland commercial that put a spicy twinkle in his eyes.

For weeks, the affable, straight-arrow insurance claims investigator – someone friends described as “Dragnet’s” Sgt. Joe Friday for his innate ability to ascertain “just the facts” and who had served for decades as an usher at St. Angela Merici Church without so much as a loose dime rolling under a kneeler unaccounted for – had been trying with no success to unearth health information on a man who had filed a hefty insurance claim for total disability.

But as Drew watched the 30-second Popeyes commercial, it wasn’t the pulsating jazz or the orange-chic chicken boxes or the dirty rice that captivated his senses.

There he was, “Mr. Flat On His Back,” waving an umbrella and strutting his stuff in a Popeyes second line, the true incarnation of Elvis, Cajun-injected with crab boil.

Nothing could explain the miraculous healing, other than chicken-fried fraud.

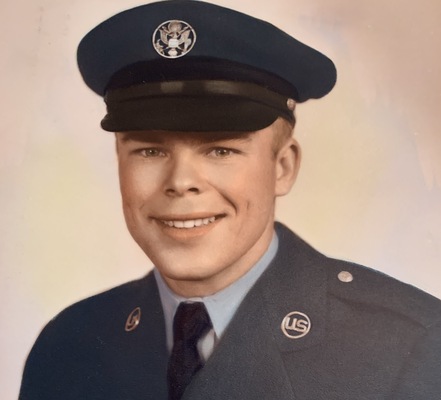

“My dad had gotten a picture of him and the basic information, and he was actually trying to reach him,” said Christopher Drew, Leon’s son, who along with his two sisters recently buried their father after his Jan. 25 death at age 90. “He said, ‘I think that’s the guy!’ Then he checked it out afterwards, and it was, indeed, the guy.”

The other bas relief on Leon’s personal Mount Rushmore of foiled insurance claims was almost too Louisiana to be believed. For a year or 18 months, a man quietly had been paying life insurance premiums on three men, none of whom was related to him and each of whom died in fairly rapid succession.

Another odd fact on the insurance form: The listed “occupation” of each of the insured was “sittin’ and waitin.’”

The $10,000 insurance policies were written by a company in Cincinnati, which might explain why in Ohio they play checkers, and why in New Orleans we have a street dedicated to chess grand master Paul Morphy.

Leon was assigned the relatively routine case and noticed, first of all, a strange resemblance to names he had read in the daily newspaper over morning coffee. That led him to the offices of The Times-Picayune, which allowed Leon access to its “morgue” of newspaper clippings.

All three men turned out to have spent their final years on death row at Angola.

“I guess for a lot of people that would have ended the case because it was pretty clear cut that the guy was a fraud,” Christopher recalled. “But my dad still called to try to set up a meeting. The insurance companies always wanted to know what people had to say, I guess. And that’s when the guy said he wasn’t going to be meeting with him. My dad told him, ‘If you expect to be collecting on those policies, you’re going to be sittin’ and waitin’ a long time.’”

Leon grew up in Harrah, Oklahoma, which he told his children had the dual distinctions of being mentioned in Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and also could be spelled the same way backwards and forwards.

When Leon was 18, his father, a part-time farmer and full-time carpenter, fell off a roof and died of internal injuries. Leon spent the year after his high school graduation trying to bring in money for his mother by selling encyclopedias.

It was on those dusty Oklahoma farms that Leon honed his skills as an interviewer, a gene that seems to have passed unaltered to his son, who in a decorated journalism career has written in-depth investigative stories for The Wall Street Journal, The Times-Picayune, the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times before returning to Louisiana in 2017 to teach at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication. Christopher also is the co-author of “Blind Man’s Bluff,” in which he and his colleagues somehow got submariners to talk about their top-secret missions during the Cold War.

It was on those dusty Oklahoma farms that Leon honed his skills as an interviewer, a gene that seems to have passed unaltered to his son, who in a decorated journalism career has written in-depth investigative stories for The Wall Street Journal, The Times-Picayune, the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times before returning to Louisiana in 2017 to teach at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication. Christopher also is the co-author of “Blind Man’s Bluff,” in which he and his colleagues somehow got submariners to talk about their top-secret missions during the Cold War. Leon told his son the key to selling encyclopedias to people who might not have had two corn cobs to rub together was to be prepared to answer the first, second and third objections.

“If the people objected for any reason – and just about everybody objected the first time – he would say, ‘I know what you mean’ in the most heartfelt way,” Christopher said. “And then he would give his pitch again. So, I tell my (journalism) students, ‘Don’t give up the first time (when someone doesn’t) answer your question.’”

Christopher sometimes accompanied his father on trips to Golden Meadow and Grand Isle, where Leon would show up unannounced at people’s houses and talk to them on the porch for an hour “until he got what he needed.”

“I’ve realized even more in the last few days that I think a lot of my success as a journalist – in knowing how to interview people – right from the start, came from listening to his stories and watching him,” Christopher said. “It was like I had a master class when I was a kid without realizing it because he could get pretty much anybody to talk. He would really listen to people. He wouldn’t pontificate. He seemed friendly. He seemed like a decent person. I think people would look at him and think, ‘You know, he’ll give me a fair shake.’”

For 40 years – until his wife Helen died of cancer in 2012 – Leon ushered at the Sunday morning Mass at St. Angela. For the last few months of Helen’s life, Leon hardly ever left her side, sleeping on a lumpy sofa bed in her hospice room.

Christopher flew down from New York every other week for four days at a time to persuade his father to go home and sleep in his own bed. “I realized how awful that sofa bed was,” Christopher said.

At the hospice facility, there was an innocuous chalkboard behind the nurses’ station.

“I’d go to sleep on that sofa at night, and ‘16’ would be the number,” Christopher said. “And then I’d wake up in the morning and the number would be ‘9.’ I finally asked, and it was what I thought it was – the census of patients. It was 16, and then by the next morning, seven had died.”

Leon had two major bouts with cancer, and in 2017, a surgery was so extensive he no longer could swallow anything more than a few spoonfuls of soft food, and he subsequently needed a feeding tube.

“His faith was part of this, too – he never complained,” Christopher said. “As much as he enjoyed eating and good food, he never complained. He was always polite. He mostly liked whatever my mom cooked, but when he didn’t like something, he would say, ‘I could take it or leave it.’ We knew that meant he preferred to ‘leave it.’ But during his 3 1/2 years on the feeding tube, he never even said, ‘I could take it or leave it.’”

When Father Beau Charbonnet, St. Angela’s pastor, visited Leon’s home to offer him Communion, he was in bed. In addition to a papal blessing on the occasion of his and Helen’s 50th anniversary, to the left of the bed was a boxed display of the dozens of yearly Christmas ornaments the parish had presented to St. Angela’s ushers.

Father Charbonnet was “so impressed that the ornaments from his ushering meant so much to him,” Christopher said.

In his final months, Leon told his children how excited he was to soon be reunited with his parents, sister and wife in heaven. Christopher called it “the best testament to his faith.”

On special occasions, Leon’s children and sitters gave him a small foretaste of the heavenly banquet: A few spoonfuls of mashed potatoes and gravy – from Popeyes.